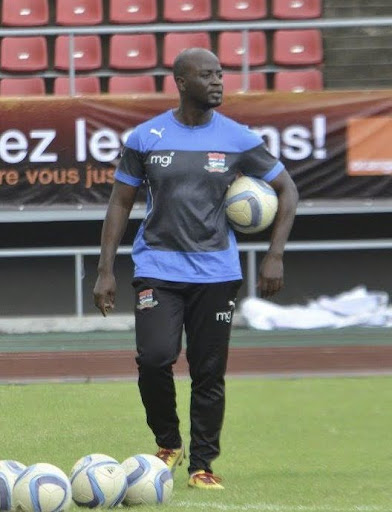

Few people in football have experienced as many different environments as Mattar M’Boge. From Loughborough University - the UK’s leading sports university - to youth national teams in The Gambia, to a role as transition coach at Danish club AC Horsens, he’s seen it all.

Over the past 20 years - and across three continents, Mattar has focused on a key but often overlooked factor in football - culture. Especially in his work with elite youth players on the brink of senior football, he’s explored what culture really means, how it shapes clubs and federations, and how to build one that lasts.

Now, he’s embarking on a new chapter. With the launch of his own consultancy, Mattar is helping clubs, federations and owners build sustainable winning football cultures.

The interview has been condensed and lightly edited for grammar and clarity.

[ Background ]

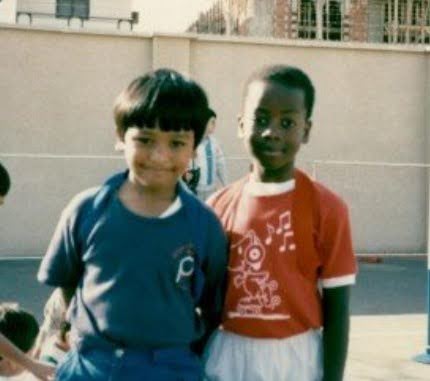

I was born in The Gambia, but actually raised in Saudi Arabia. My dad had a job out there when I was very young, so I grew up there until the age of 17. I was always involved in sport and was captain of my youth teams in Jeddah. For sure, football’s always been a big part of my life.

But my parents wanted me to focus on education. In school, I had been following the British curriculum and went to the UK to do my A levels and go to university as well.

That's where I was able to play for the university side and also where I started as a coach, going through the badges and getting my grounding. Loughborough University is the top university for sports related subjects in the UK and probably the world. It was a great environment in terms of facilities, access to sports science, nutrition and all sorts of things. It was a great place to start.

Then, from there I started a full-time job in marketing and advertising, working with marketing agencies, going for proposals, winning pitches, and having that competitive environment. In a sense, I was able to take some lessons from there into my coaching.

[ The Gambia and going full time ]

After years of balancing corporate work with part-time coaching, I reached a crossroads.

I went back to The Gambia and volunteered with the U20 national team. Then I was hired by a club team and eventually won the league. The Federation interviewed me and appointed me to the U17 Head Coach national team job. Eventually, I took over the U20s. I had a lot of success there and moved up to the U23s and was also working as an assistant with the senior team.

I was traveling a lot for study visits around Europe to see coaches in action and learn from them. I went over to the States for one of these visits and DC United had a position available with their U23 team, Loudoun United, and I took that position as well.

There was a little push and pull between the federation, and in the end, I was given an ultimatum. It’s normal in football as a player to play for your national team while still playing for your club, so this was a similar arrangement. But finally, I had to pick one and chose the States for family reasons. When I moved out there, I also became the U19 head coach for DC United.

We did well there and I really enjoyed it. A lot of the players have gone on to Ivy League schools to play their soccer and a few have gone into the professional game. So I’m proud of the work I did, both in The Gambia and in America.

[ Was there a ‘turning point’ or what led to your decision to quit your job in marketing and move into coaching full time? ]

Yeah, there was a turning point. I took a senior position, as a director of business development for a company in London. I explained to my boss at the time that I needed to leave at 5pm in order to catch the tube up to Barnet - bearing in mind, we finished at 5:30. We’d start a 9 but I’d come in at 8 - that’s always me, I always came in early! Anyway, it came to a point where I would leave at 5 and some of the others in the company were like, ‘where’s he going?’. So, they stopped allowing me to go early.

I remember leaving at 5:30 and arriving late for the training session and the players were asking me, ‘what happened?’ or, ‘how come you’re late?’. I told them I was at work! And the players said, ‘what do you mean? We thought this was your work!’

The light bulb just went off. This is what I want to do. I want to be coaching.

There was also a ceiling in terms of ethnic minority coaches at times and I just felt like I was at a point where I just wanted to head back to The Gambia. It was a mixture of things to try to give back while going forward with my career.

And then in the end, I ended up staying for 8 years! I got everything that I wanted from there - in terms of coaching, I was able to go full time, have success, and ‘the rest is history’.

"This is what I want to do. I want to be coaching"

[ Transition coach at AC Horsens ]

Then I got an opportunity to go to Horsens in Denmark where I was head-hunted for the role. It was through a friend I’d worked with previously within African football and he was basically the architect for the whole project. The club was looking for someone who would understand both the European environment and the African players’ backgrounds. So, I was employed as a transition coach. Together with my wife, who joined the player care team, we embraced the challenge of relocating to Denmark and supporting the players both on and off the pitch.

We dealt with a lot of culture topics in this role. There were so many things that weren’t aligned, too many voices that wanted to be heard without a consistent culture or standard.

One example I can give is the club captain, he’d been there for nearly 8 years and was the culture setter. They tried to take the captaincy off him and take him out of the team. The fans really weren’t having any of it, there were even protests. That’s an example of a challenging moment that highlighted how important it is to align decisions with the club culture and communicate them clearly. If the culture breaks down, it can affect performance.

A big part of my role was to help foreign players integrate and settle at the club and in the country. We were pulling players from Africa and also from America, from MLS or the USL.

We faced some of those challenges as well. I think Denmark is a very progressive society, everything works, everything is digital, they have a lifestyle where people are happy. When you look at the school system my kids were in, I’ve never seen them so happy at school! But it’s still a challenge to accept foreigners, there were just barriers there.

Some of it was probably the city we lived in, Horsens, is a place with an older and more traditional population who had not really been exposed to international environments. I think maybe if we were in Copenhagen or Aarhus, it might have been different.

I had to look at how being in a city that’s not so cosmopolitan, not so open, affects the culture. How does it affect the staff and the players? We had a lot of African players who sometimes found it challenging when they went out into the town for a walk or to do their shopping.

At the same time, we signed about 15 new players. 15 in, 15 out. I mean, that's gonna have an effect on your culture because even the players who haven’t been sold are looking around wondering if they’re next.

My experience there, where our performance didn’t reflect the potential we had in terms of resources, made me reflect on deeper cultural and structural factors. I’ve experienced environments where small misalignments had a big impact and that’s why I launched my consultancy: to help clubs and federations get these fundamentals right.

[ More specifically, what does a transition coach actually do on a day to day basis? How common is a role like this? ]

It’s becoming a common path. Often it’s just titled differently, at Liverpool, for example, Vítor Matos was ‘individual player development coach’. You are a bridge between the first team and the second team, whether it’s the U21s or the U19s.

You’re working with the best talent from those teams, giving them individual sessions, videos and just giving them that care and attention they need to try and get to the first team. And when they're in that first team environment, when they’ve played a couple of games, the work continues in terms of establishing them as a senior player.

It’s about being a constant and consistent presence. Where a lot of things might be changing - including the head coach - it can be a lot for young players to deal with at once.

I’ve always focused on the cultural aspect. I try to prepare these young players, 17, 18 years old, they’re going to go into an environment where they’re trying to take someone’s job. Someone in that first team locker room, they see you coming, it’s not like they’re not aware or they don’t know what position you play, they know all about you - and you’ll see it. I’ve seen training sessions be quite brutal where the younger players struggle because they can’t navigate or handle the shouts and screams from their teammates.

Because of all these factors, I’ll be there as a presence on the training ground, working with the coaches on the first team and also the youth teams, being that consistent presence. I want the players to know I’m on their side, I’m fighting their corner, that it’s okay to make a mistake or not have a great day, but we need to keep working and working.

The more I delved into the role, the more I’m convinced this is how it has to be. This is a necessity for all clubs if they want to bring through their best young talent. I don’t think there’s been enough resources or attention allocated to this role. It’s a big challenge for young players to be thrown into the jungle of the first team dressing room, especially when the culture isn’t really good.

My time at AC Horsens came to a close in mid-2025, following a period of professional misalignment and organizational change. While the circumstances tested my resolve, they also strengthened my commitment to ethical leadership and football environments built on merit and trust. Every role leaves a mark and this one taught me the importance of standing firm in your values, especially when navigating complex club dynamics.

"I try to prepare these young players, 17, 18 years old, they’re going to go into an environment where they’re trying to take someone’s job"

[ Why have you focused most of your career on these age groups just before senior football? ]

When I reflect on it - and I’ve worked with younger and older players also - it goes back to my personality. As a coach, I’m quite authentic and intense. I have high demands!

At the very, very top level with first team players, some want this, some don’t. It’s a mixed bag. I’ve worked with players in first team environments who just don’t like this and try to find a way for you to not be there anymore.

I found that this is the sweet spot. These young players, they want that guidance. They want someone to tell them the truth. At this stage, they want somebody who is gonna be demanding, because there’s a big gap from elite academy to the first team.

It’s a much more conducive work environment when everyone is pushing for the same thing - to get to the next level.

And I've had such joy working with players in this age group. Players in The Gambia in that professional development phase, 17 to 21, who made the transition to Europe and got a pro contract. When the intensity and demand is higher, there aren’t many surprises.

I can also give them information about what they’re going to find with their teammates. I’m going to try to advise them to stay humble and give some warnings, like don’t go in there with flashy earrings, dyed blonde hair and stylish clothes because you’re just going to put a target on yourself. Not everyone listens! But in that last step in the professional development phase, they’re more receptive and I’m more motivated and energized to work with that group.

And, it’s very rewarding to get messages from players I’ve worked with, thanking me for preparing them and playing a part in their career.

[ You’ve coached in a lot of very different countries, what are some of the big learnings or differences about the role culture plays in football development? ]

I worked with Nigeria, and I remember Victor Osimhen with the U23s. Seeing Osimhen when he was 17 or 18, if you’d told me he was going to become the most expensive African player ever, I’d tell you, no way, 0%. But his success is because of his mentality and his background. When he was 13, he was selling water on the streets of Lagos.

A lot of players coming from Africa had to start working early, they come from these environments. Training is everything for them, the game is everything, and the contract is everything.

I find that working in America, in Denmark, in the UK, players in their same age group, they've not had to work in their life. They've not had to go out in the streets and sell water. It's just really really different, I mean, I once coached a player who came from a very privileged background, a Porsche for his 18th birthday. It really brought home how different the starting points can be.

When you mix those cultures together, you have a guy who's dying for the game and a player who, whether he makes it in the game or not, they’re going to be fine - he’s going to go to college, maybe he will become a lawyer or a doctor. When these two players go in for a 50/50 in training, the players from the West, I’d say they’re more often like, ‘hey, take it easy’ but the African players are like, ‘what are you telling me to take it easy for? If I don’t make it, I’m going to have to go back to my country and wash cars for a living’.

Of course, every player is unique and there are driven players in every culture but broadly speaking, the environments they come from shape their hunger and resilience differently. We had the Danish U-19 national team coach come in for a session and he told the team how he was astonished by the high intensity levels and the hard tackles flying in, something that was rare to see.

And then, when they become professional and have earned a contract in Europe, African players are often earning more money than their parents at home. The family relies on the player at 18 or 19 or 20 for their living. He has to send money back, whenever he comes home, people are asking, ‘can you get me this and that?’. They’re forced to grow up really quickly. It’s much rarer for players in America or Europe to be in this situation. So that’s another dynamic and ‘clash’ in terms of culture.

[ Is there a way to ‘instill’ some of this culture or drive into, let’s say, a youth player in the European or American suburbs? ]

We've discussed it a lot. We talked about having exchange visits. More practically, we try to make training as challenging as possible, so they ‘fail’ a lot and have to find their own solutions and try to build resilience that way.

Another aspect is to get them to do a lot of work with the community. Whether it’s school or the local council, just doing jobs here and there. They don’t need the money but being out there doing hard work, things like cleaning the stadium, for example. They never want to do it - and sometimes end up hating you for it! But it can help them build up some resolve and help them say, ‘wow, okay, I’m paid, I have a contract to kick a football around - there are a lot of harder jobs out there, so I’m grateful and thankful to be able to do this’. Some take it on board like this and it gives them motivation to push themselves to make sure they don’t fall through the cracks.

We also tried to share stories. Players share their backgrounds. I've seen players in tears when they hear a story of another player of what they've had to go through. This can help with empathy and understanding.

But ultimately, it’s difficult to replicate. The US and Europe are far more developed right now than Africa, so you don’t have many players who go through that kind of hardship. The whole system in Denmark, for example, is built so you don’t have these hardships - and that’s a really good thing for society!

The question is then, where can players get that resilience from? Where do they get that fire? Where do they get that adversity they can fight through? I think that will eventually serve them well in anything they do, it doesn’t have to be football.

[ Toni Kroos recently said on his podcast that the Real Madrid players would have laughed at Hansi Flick (because he’s strict about things like being on time to meetings) but also acknowledged that that’s just one way of doing things, it was different but not ‘better’ or ‘worse’. I think that’s an interesting point, ‘good’ culture can look different in different places, are there some ‘universal’ signs of good or bad culture in football? ]

Yeah, for sure. There are so many examples I can give of a bad culture. But just to give one that you can see easily. Usually, after a training session, the players go for lunch. Are people chilling, going to the games room or just having a chat about things? Is it natural? Or are people rushing to eat or even taking a takeaway? Those are often easy signs to see.

Another example of good culture - one that I saw that made me very proud. Players often come to the training ground with earrings or bracelets or a watch or something. A player from Guinea was speaking to a Danish player who went, ‘hey, your earrings!’ and ‘thanks for reminding me!’. The coach didn’t have to say anything, it’s the players who are - not ‘policing’ but taking care of themselves. If someone is late, they should have to answer to their teammates, not the coach.

For sure there are tons of other examples of bad culture. A lot of the time, a club might not see it or be aware of it but they might also miss out on players. Players who will turn down a very good offer financially because they’ve heard from players in the current locker room, telling them it’s a toxic environment.

Some will come anyway, I think often they’re just looking after themselves in terms of their career, but when someone is just there for the money, because they just doubled their salary, that also adds to the negative culture. I’ve seen this exact scenario play out several times.

[ Are we still learning about culture in football? Are there things that were ‘good’ in the past that are ‘bad’ now? (I think I’ve heard a million ex-footballers lament the ‘loss’ of the bootroom tasks for young players…) ]

For sure. To some extent, society forces us to treat the players - and people in general - with kid gloves in a way. Like you said, the bootroom - where academy players would be responsible for washing the boots - I don’t see that anymore. Apparently, that’s not allowed.

A long, long time ago, I used to tell my players if they were late, they would have to do some kind of simple forfeit. I don’t think you could do that now. In America, I saw a coach who would make players do extra running after training. I was the one who said you can’t do that, that’s physical abuse. They’ve done the session and you’re making them run until they’re sick!

It’s really a balance. We’re still learning about culture. Every day, there are different things coming in about safeguarding and player welfare - and rightfully! You can’t bully players, you can’t force them to do extra runs, you have to look after feelings. A lot of that is an old school thing that coaches used to do, but you can’t anymore.

Now, the best experience has been when the players are the ones who set the culture. They hold themselves accountable.

Realistically, the sporting director is the leader, they are the ‘front’ of the culture, the one who has to say, ‘this is what we are about, this is what the club stands for’.

Unfortunately, a lot of the time, they aren’t. I’m not even necessarily blaming the sporting directors. Sometimes I look at the owners or the people hiring the sporting directors, and wonder, are they holding them accountable?

What did they bring them on board for? I think often it’s because they are good at transfers, signing players, negotiating with agents and driving a hard bargain when selling players. Okay, that’s great, but if they’re not setting the culture - or empowering people to set the culture - and it’s just left up in the air, everything collapses. It has to come from the top.

If the culture is bad or not set, it trickles all the way down. I was at a club where the U17s were hearing about all this stuff going on in the first team, and it was really affecting them. Players saying things like, ‘do I really want to stay here in this environment?’.

The reverse is also true though. If things are really good at the top, then you have the U21s, U19s, U17s, etc - they’re like, ‘I can’t wait to get into that environment’ and it really drives them and motivates everyone.

[ You’ve just started Champion Sport Consulting, what is it? ]

For me, the motivation came from my experience as a coach, having worked predominantly on the field, on the training ground. My wife has also worked in football administration, and we've seen a constant theme - if the strategy and direction of the federation or the club isn’t set in stone and aligned throughout the organization, there are going to be clashes and things will fall apart.

We try to connect everything together. The name ‘Champion Sport’ is about building an environment geared to win, not just once or twice, but to keep on winning.

We find out what success looks like for each organization, which direction they want to go and help to disseminate that message from the directors to all the staff, so that it gets all the way down to the players and coaches. We’ve seen firsthand that if this isn’t done, it can really affect performance on the field.

Aside from that, we also have the technical expertise, especially in terms of transition coaching, to set up strategies to build that pathway into the first team. A lot of the time, you might have a talented 18 year old who gets called into the first team and then sits on the bench for the whole season. Of course, he won’t develop, he needs to play! If there are 3 senior pros in his position, the head coach, who is chasing results, is more inclined to go for the ‘safe bets’ and the kid ends up 4th choice and playing in U19 games. For example, we helped one club reduce first-team transition failure rates by creating a dual-training schedule and a weekly mentorship programme.

So setting these pathways is really important so you don’t ‘cannibalize’ your talent and give them the best opportunity to flourish.

Those are the main areas we look at. It’s a holistic approach to make sure that federations, clubs and national teams are built for success.

"The name ‘Champion Sport’ is about building an environment geared to win, not just once or twice, but to keep on winning"

[ Are you involved with the actual implementation of these strategies? ]

Yes, we want to be partners with clubs and national teams. We want to be part of the implementation. We want to be held to account and judged on the results, we don’t just say, ‘here you go!’ and leave them alone.

Usually, the client will give us a ‘roadmap’ in terms of what they want. We’re there to listen, tweak and tailor it to them. In the implementation phase, we are on the ground to make sure things are fulfilled. We have the experience and the foresight to see, ‘wait a minute, there’s a danger here we need to deal with’. Being on the ground is how we can see - and fix - these problems.